Systems & Muscles

Answer Key

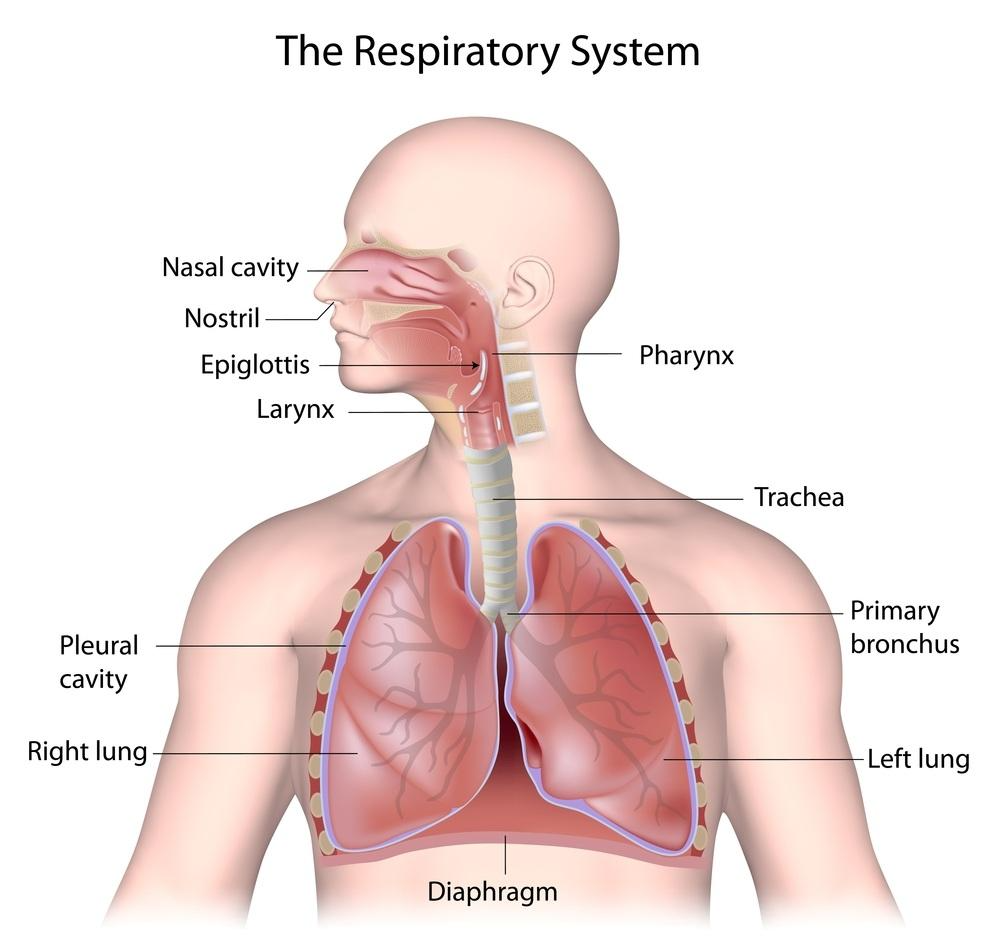

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

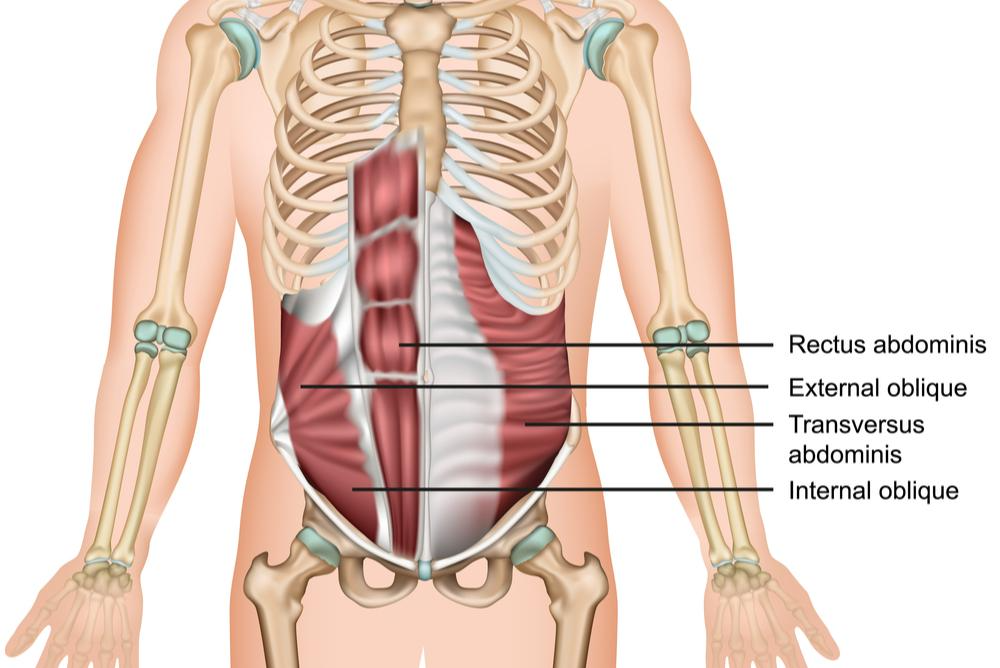

ABDOMINALS

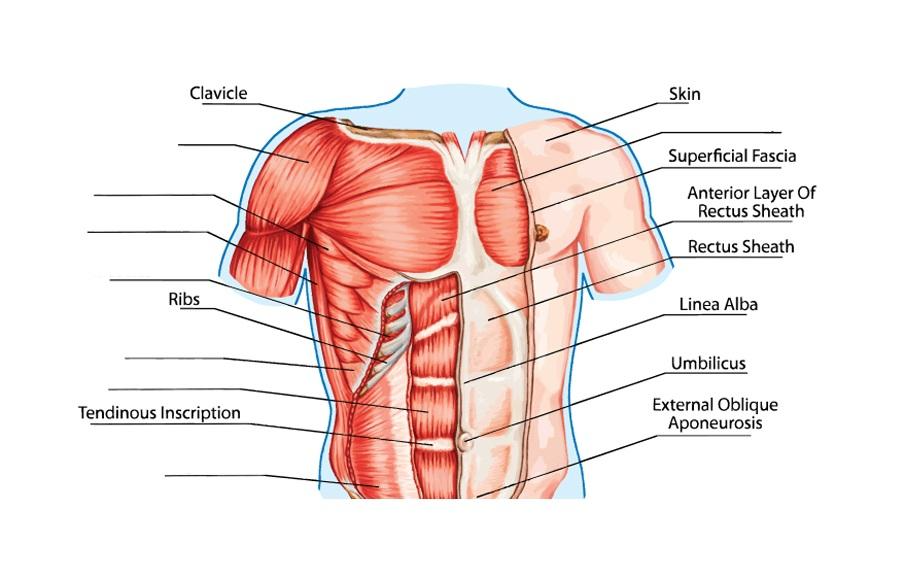

UPPER BODY MUSCLES

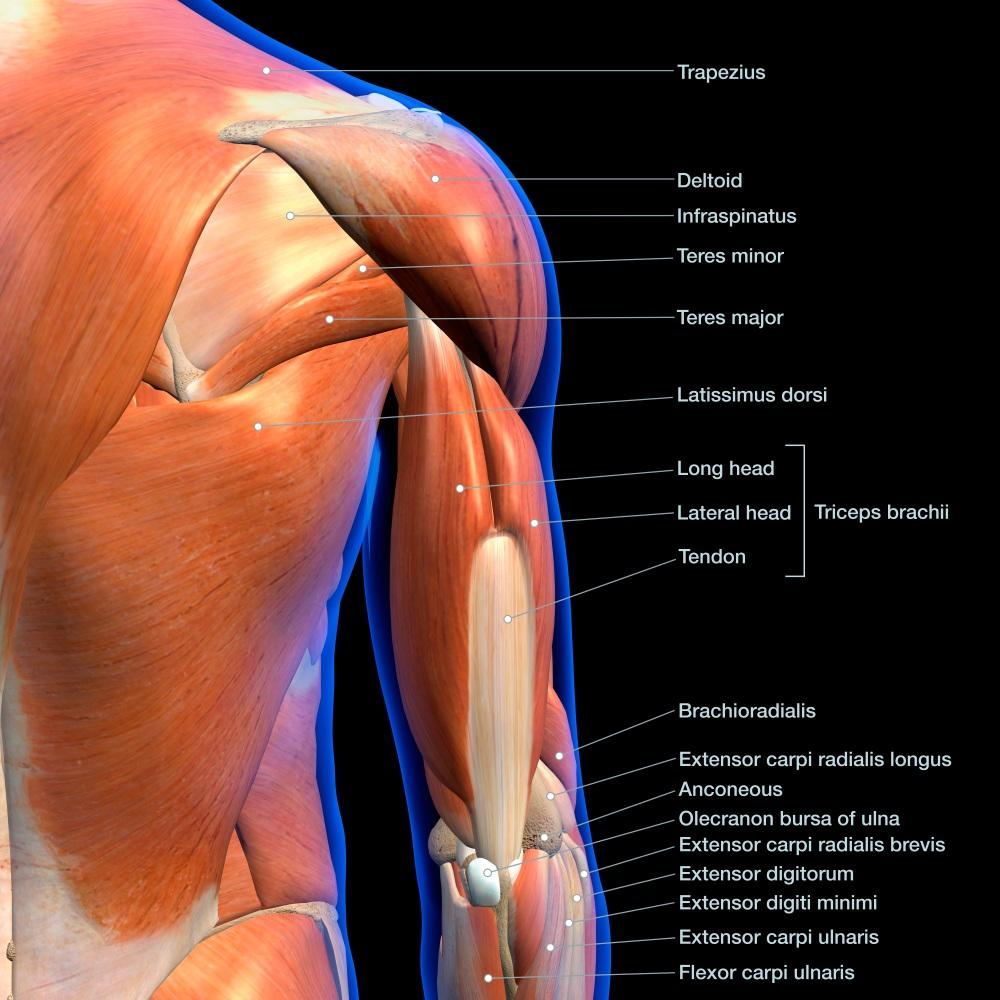

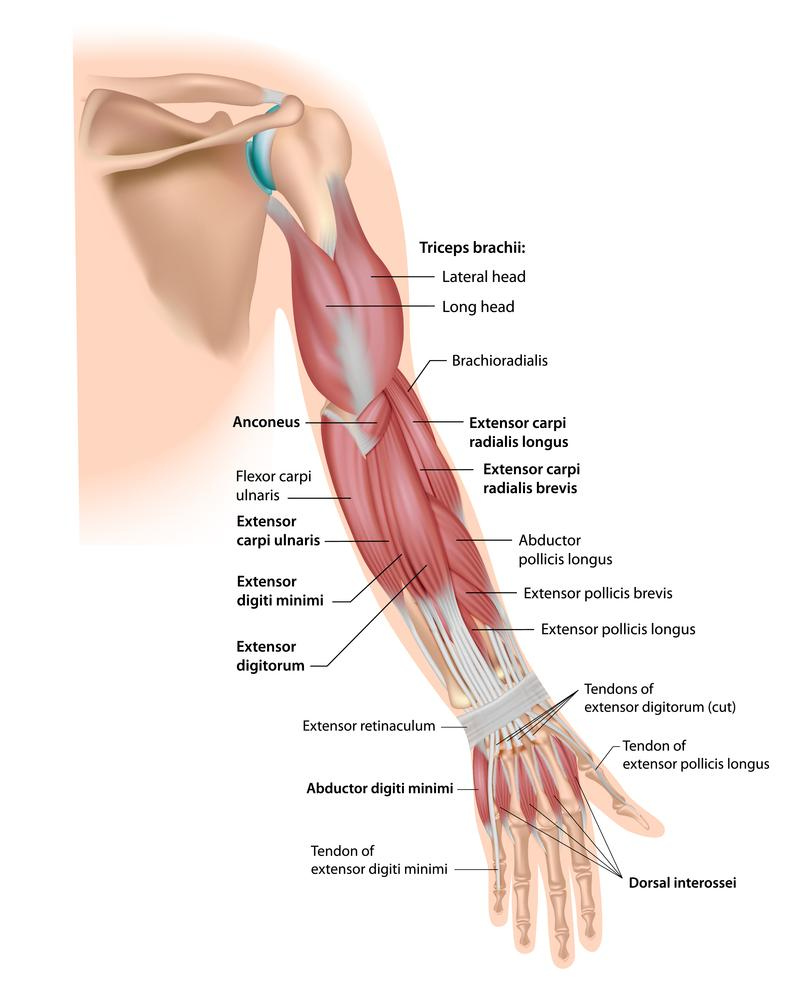

SHOULDER & ARM

SHOULDER: DELTOIDS

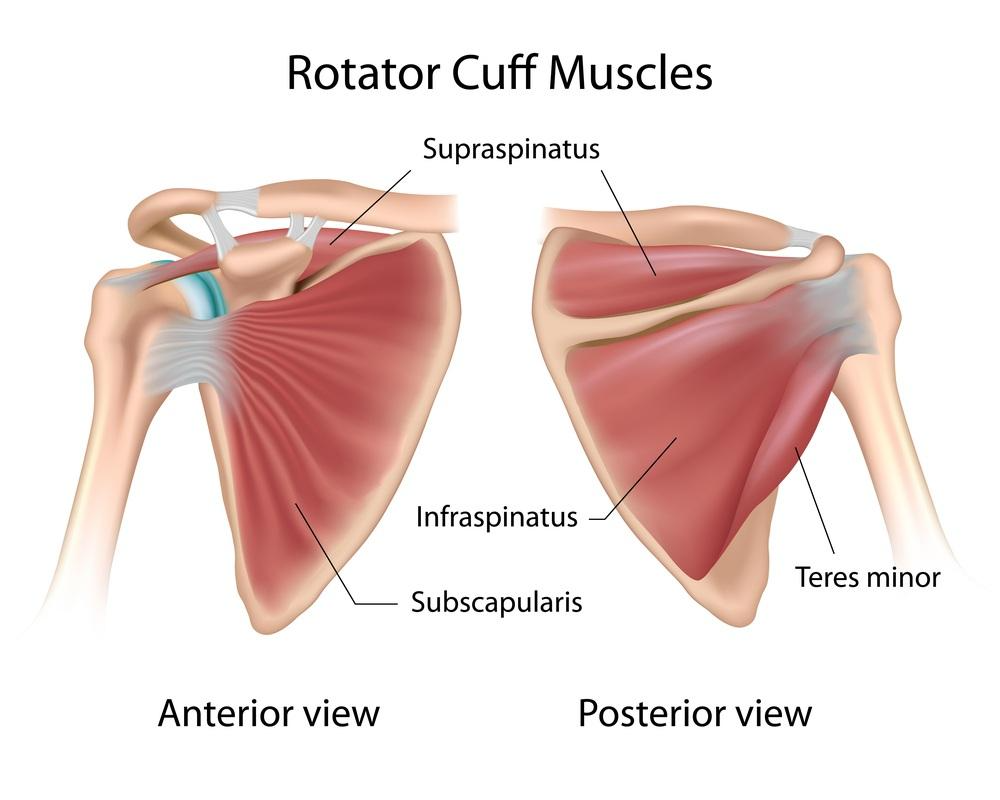

ROTATOR CUFF

ARM

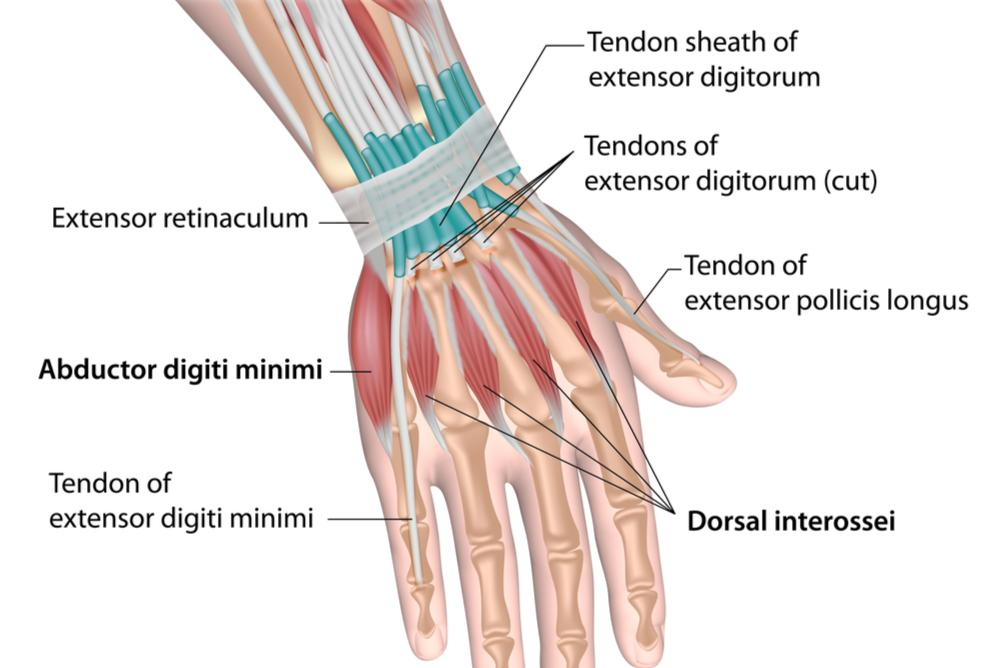

WRIST & HAND

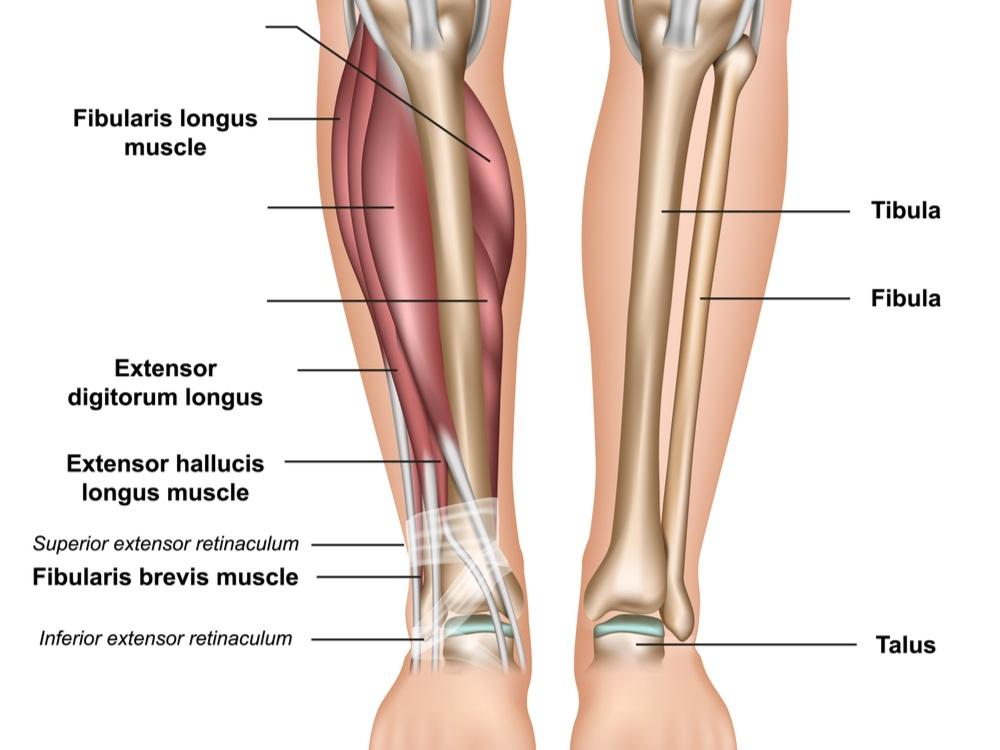

LOWER LEG MUSCLES

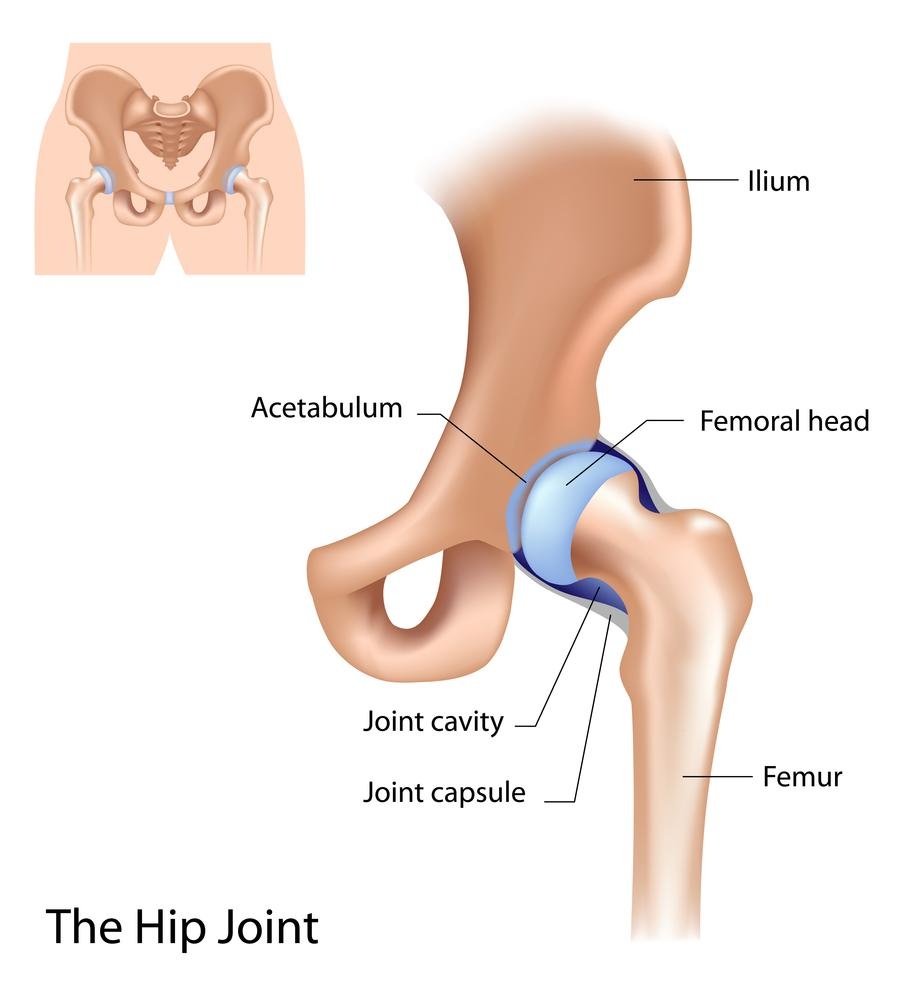

HIP JOINT

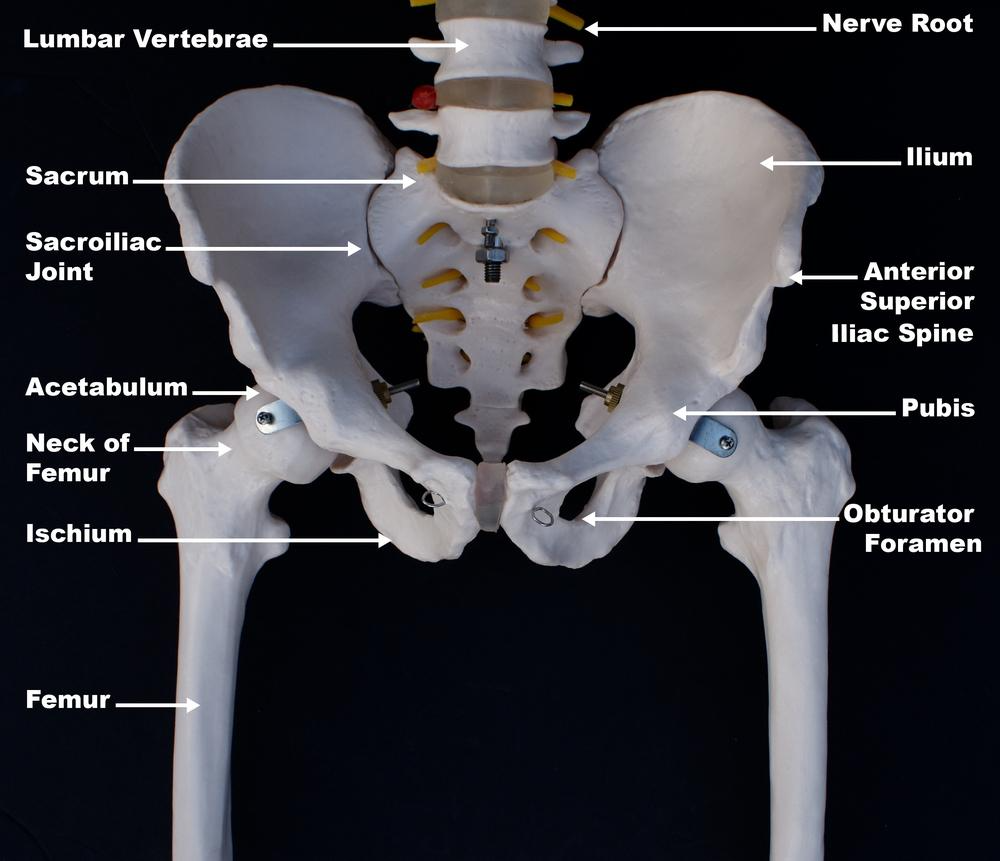

SACROILIAC JOINT

WHOLE BODY- MUSCLES & BONES

Musculoskeletal System Intro

Answer Key

Vocabulary Mix & Match

| APPENDICULAR SKELETON (1) | 🡪 | (D) | The bones attached or appended to the axial skeleton (spine, skull and rib cage); bones of the upper and lower limbs plus the shoulder and pelvic girdles |

| AXIAL SKELETON (2) | 🡪 | (B) | Spine, skull and rib cage |

| BALL AND SOCKET JOINT (3) | 🡪 | (I) | A type of joint that allows for a wide range of movement, including rotation |

| BONES (4) | 🡪 | (F) | Living tissues that form the body’s structural framework |

| HINGE JOINT (5) | 🡪 | (C) | A type of joint that provides greater stability than other types |

| JOINT (6) | 🡪 | (H) | Junction / connecting point between bones |

| MUSCLE (7) | 🡪 | (G) | A band or bundle of fibrous tissue that has the ability to contract; attached to bone by tendons |

| MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM (8) | 🡪 | (E) | Gives humans the ability to move via bones, muscles and connective tissue |

| SYNOVIAL JOINT (9) | 🡪 | (A) | The most common type of joint in the body; freely movable |

- What is included in the musculoskeletal system and what does it do?

- The musculoskeletal system gives humans the ability to move using their muscular and skeletal systems.

- It includes bones, muscles and connective tissue. (While bones and connective tissue are often described separately for learning purposes, expert sources explain that bones are a type of connective tissue.)

- In addition to enabling body movement, the musculoskeletal system provides form, support and stability, protects vital organs, stores minerals such as calcium, produces red blood cells, moves blood and food, and generates body heat.

- What is a bone?

- Bones are living tissues that form the body’s structural framework.

- Bones are defined as “the hard, rigid form of connective tissue constituting most of the skeleton of vertebrates, composed chiefly of calcium salts.” (Medical Dictionary)

- Bones are comprised of calcium salts, connective tissues, cells and blood vessels.

- What is meant by the axial skeleton?

- The axial skeleton refers to the spine, skull and rib cage.

- What is the appendicular skeleton?

- The appendicular skeleton refers to the upper and lower extremities.

- What is the function of bones?

- Bones provide a framework for muscles and other tissues.

- Bones protect internal organs.

- Bones enable body movements.

- Bones store essential minerals such as calcium. And bones store lipids that serve as an energy reservoir.

- Marrow at the center of large bones produces red blood cells.

- What is a joint?

- Joints are junctions / connecting points between bones.

- For example, the knee joint is the point of connection between the thigh bone and the shin bone.

- Define muscle.

- A band or bundle of fibrous tissues in a human or animal body that has the ability to contract, producing movement in or maintaining the position of parts of the body.

- What are the three types of muscles in the body?

- Smooth Muscle — muscles that line organs, blood vessels and the digestive tract

- Cardiac Muscle — specialized muscles within the heart for pushing blood through the arteries and veins

- Skeletal Muscle — muscles for moving bones

- What is the main function of muscles?

- The main function of the muscular system is movement.

- Describe four additional functions of muscles.

- Muscles maintain posture and body position. This includes contraction to hold the body still.

- Muscles are responsible for breathing, heart function and much of the circulatory system.

- Muscles move substances such as blood and food from one part of the body to another.

- Muscles generate body heat.

- What is connective tissue? What are some examples of types of connective tissue?

- Connective tissue is a fibrous type of body tissue that connects, supports, binds, or separates other tissues or organs.

- Types of connective tissue include tendons, ligaments, joint capsules and fascia.

- What is a ligament? A tendon?

- Ligaments connect bones together at the joint. They strengthen and stabilize joints.

- Tendons attach muscle to bone.

Connective Tissue, Fascia

Answer Key

Vocabulary Mix & Match

| CONNECTIVE TISSUE (1) | 🡪 | (C) | A fibrous type of body tissue that connects, supports, binds, or separates other tissues or organs | |

| 🡪 | (D) | A type of connective tissue that is a sheet or band of fibrous tissue, giving contour and structure to the body | ||

| FASCIA (2) | 🡪 | (B) | A type of connective tissue that surrounds synovial joints | |

| 🡪 | (A) | A type of connective tissue that connects bones together at the joint | ||

| JOINT CAPSULE (3) | 🡪 | (F) | Muscles and surrounding tissues | |

| LIGAMENT (4) | 🡪 | (E) | A type of connective tissue that attaches muscle to bone | |

- What is connective tissue?

- Connective tissue is a fibrous type of body tissue that connects, supports, binds, or separates other tissues or organs.

- Some connective tissues are soft and rubbery; some are hard and rigid.

- Connective tissue fibers contain a protein called collagen. Collagen can be stretched “like a really, really, really stiff rubber band.” (Jules Mitchell)

- What are some examples of types of connective tissue?

- Tendons

- Ligaments

- Joint capsules

- Fascia

- What are some functions of connective tissue?

- Connective tissue supports and connects internal organs.

- It forms bones and the walls of blood vessels.

- It attaches muscles to bones.

- Connective tissue replaces tissues following injury (e.g. scar tissue).

- Fascia helps the body sense itself.

- Energy Medicine experts explain fascia as the connection between the physical and energetic body.

- What is a tendon?

- Tendons attach muscle to bone.

- “More accurately, they connect muscles to the periosteum — the connective tissue which surrounds the bone.” (Andrew Biel)

- Tendons come in a variety of shapes and sizes.

- Fibers of tendons are arranged in long, straight lines.

- They are “smooth, tough” and have an “almost resilient feel to them.” (Andrew Biel)

- What is a ligament?

- Ligaments connect bones together at the joint.

- They strengthen and stabilize joints.

- Unlike a tendon’s parallel fibers, a ligament’s fibers are more unevenly arranged.

- Ligaments can be stretched but are not very elastic.

- What is a joint capsule?

- Connective tissue surrounding synovial joints is called a joint capsule.

- It serves as a container for synovial fluid (the slippery fluid that fills most joints).

- Joint capsules provide a tough covering of tissue where ligaments and tendons can insert.

- “And, of special interest to us here, they and their associated ligaments provide about half the total resistance to movement.” (David Coulter)

- Define fascia.

- In Latin, “fascia” means “band,” “bandage,” or “bundle.”

- Fascia is a sheet or band of fibrous tissue. It varies in thickness and density.

- “You would be safe to think of fascia as any connective tissue that doesn’t have a more specific name.” (Bernie Clark)

- In more technical sources, fascia is broken down into superficial fascia, deep fascia and visceral fascia. (Radiology Journal)

- “Fascia is made up of a matrix of material, almost like a gel, that contains fewer cells in proportion to its overall structure, making it both pliable and supportive.” (Baxter Bell)

- Fascia gives contour and structure to the body.

- Explain fascia using descriptive phrases that help students to visualize and get a clearer sense for this pervasive tissue.

- Without connective tissue, the rest of the body “would flatten down on the floor like a hairy, lumpy pancake.”

- It “surrounds, connects and supports muscles, organs, bones, tendons, ligaments and other structures of the body. Similar to the membrane around each section of an orange, fascia both separates and connects body parts at the same time. Containing nerves, these tissues also serve as a layer of protection and body awareness.” (Allison Candelaria)

- It is often described as a “body envelope” or “sac” that “permeates through and around every nook of the body.”

- Baxter Bell describes it as being “like a specialized kind of plastic wrap.”

- Fascia is full of sensory nerve endings that are in constant communication with the brain. What is this communication about?

- Fascia is in constant communication with the brain about the body’s position in space.

- From an Energy Medicine perspective, what is a function of fascia?

- In Energy Medicine, the “living matrix” or “extracellular matrix” refers to the system that physically and energetically connects all of our parts together. The matrix is essentially our connective tissue.

- What is meant by the term “myofascia?” What is the significance of this term?

- The word “myofascia” refers to muscles (myo) and surrounding tissues (fascia).

- The word is used to help orient our thinking to the “inseparable nature” of muscle tissue and its connective tissue.

- How does the “myofascial meridian theory” differ from the traditional anatomy model?

- Thomas Myers has been a key expert communicating about this critical topic. (See Anatomy Trains.)

- The MyoFascial Meridian Theory highlights the inaccuracy of seeing muscles as isolated units, separate from one another. It helps us to envision the interconnected whole that the body is.

- For more on application of this concept, see Flexibility & Stretching: Issues & Teaching Techniques.

Location & Movement Terminology

Answer Key

- What is flexion and extension?

- Flexion — Decreases joint angle (Usually moves a body part forward except in the case of the knee which moves backward)

- Extension — Returns joint to resting position

- What is hyperextension?

- Moving beyond normal, healthy range of motion

- What is meant by lateral and medial?

- Lateral – Away from the midline

- Medial – Toward the midline

- Describe adduction and abduction.

- Adduction — Moves a part of the body toward the midline

- Abduction — Moves a body part away from the midline

- What is meant by internal and external rotation?

- Internal / Medial Rotation — Moves toward the midline

- External / Lateral Rotation — Moves away from the midline

- What is the meaning of anterior and posterior?

- Anterior – In front

- Posterior – Behind

- What is meant by distal and proximal?

- Distal – Away from, farther from the origin

- Proximal – Near, closer to the origin

- What is meant in anatomy by superior and inferior?

- Superior – Above, over

- Inferior – Below, under

- For what purpose related to asana has Andrey Lappa described movement differently?

- Traditional asanas use some of, but not all, the possible types of movements. In addition, traditional asanas tend to utilize an overabundance of active stretches.

- To address his findings, Lappa developed additional practices derived from other movement modalities.

- What are the three planes of motion called? What type of movement happens in each?

Sagittal Plane

- Divides the body into left and right halves

- Any forward and backward movement occurs in the sagittal plane

Frontal or Coronal Plane

- Divides the body into front and back halves

- Any lateral (side) movement occurs in the coronal plane

Transverse Plane

- Divides the body into top and bottom halves

- Rotational movement occurs in the transverse plane

Muscle Movement & Contraction

Answer Key

Vocabulary Mix & Match

| AGONIST (1) | 🡪 | (B) | The muscle providing the predominant contraction for a movement |

| AGONIST (2) | 🡪 | (F) | Antagonist Relationship — When one muscle contracts, another muscle stretches |

| ANTAGONIST (3) | 🡪 | (K) | The muscle that performs motion in the opposite direction of the agonist; it stretches passively |

| CONCENTRIC CONTRACTION (4) | 🡪 | (H) | Muscle contraction causing movement against gravity; muscle actively shortens |

| ECCENTRIC CONTRACTION (5) | 🡪 | (A) | Muscle contraction causing a slow down of movement with gravity; muscle actively lengthens |

| FIXATOR MUSCLE (5) | 🡪 | (N) | Another name for stabilizer |

| INSERTION (7) | 🡪 | (L) | The distal (away) attachment of muscle to bone; on the bone that is most generally moved |

| ISOMETRIC CONTRACTION (8) | 🡪 | (G) | Muscle contraction with no movement (muscle doesn’t change length); also called static contraction |

| ISOTONIC CONTRACTION (9) | 🡪 | (M) | Muscle contraction with movement |

| MUSCLE CONTRACTION (10) | 🡪 | (D) | The activation of tension in muscle fibers |

| ORIGIN (11) | 🡪 | (O) | The proximal (near) attachment of muscle to bone; on the bone that is relatively stationary |

| ORIGIN & INSERTION POINTS (12) | 🡪 | ( I ) | The places where muscles are attached to bones in relation to a movement at a joint |

| PRIME MOVER (13) | 🡪 | (P) | Another name for agonist muscle |

| RECIPROCAL INHIBITION (14) | 🡪 | (J) | An unconscious spinal reflex that causes the antagonist muscle to relax when the agonist muscle contracts |

| STABILIZER MUSCLE (15) | 🡪 | (C) | The muscle that fixes part of the body so that movement can occur |

| SYNERGIST MUSCLES (16) | 🡪 | (E) | Muscles that contract along with the prime mover to help carry out a motion |

- What is the purpose of muscle?

- Muscles provide the force behind movement.

- Muscles are the only tissue in the body that have the ability to contract and therefore move other parts of the body.

- Our focus here is on the way that muscles move bones. In addition, muscles are also responsible for: movement of blood and lymph, expansion and contraction of the lungs, and movement of solids and fluids through the digestive tract.

- How does movement happen?

- Movement is produced by muscle fiber (bundles of specialized cells) changing shape (contracting or relaxing).

- Muscle fibers contract in response to the Central Nervous System.

- The force of the contraction is transmitted to the fascial elements surrounding the muscles and eventually on to the bones, moving the joint. (Ray Long)

- What is muscle cramping? Why might a muscle cramp?

- Muscle cramping is sudden, involuntary muscle contraction which causes pain.

- Causes can include pregnancy, medications, liver disease and exercise.

- In the case of exercise or movement, the cause of the cramp may be oxygen deprivation.

- What might help with muscle cramping?

- Deep breathing and bringing circulation to the area may help to prevent or resolve cramping.

- What is muscle contraction?

- Muscle contraction is the activation of tension in muscle fibers.

- Some sources incorrectly define muscle contraction as the muscle shortening; in fact, the muscle may lengthen, shorten or stay the same.

- How do origin and insertion points relate to muscle contraction?

- As muscles contract, usually one end of the muscle remains fixed and the other end moves.

- The attachment site that doesn’t move during contraction is known as the origin; the attachment site that moves is known as the insertion.

- Different movements can cause a “functional reversal” of the origin and insertion points for a muscle.

- What are three types of muscle contraction and an example for each?

Concentric Contraction

- Causes movement against gravity

- Muscle actively shortens

- Example: raising weight during a bicep curl

- Asana Example: Raising arms forward up—anterior deltoid and biceps contract concentrically

Eccentric Contraction

- Slow down movement with gravity

- Muscle actively lengthens

- Example: walking (quad actively lengthening)

- Asana Example: Controlled lowering of arms from overhead down to sides—biceps and anterior deltoid contract eccentrically

Isometric Contraction

- “Static contraction”

- Muscle activated but no change in length

- Bones do not move

- Example: Carrying an object in front of you; or muscle attempts to push or pull something immovable

- Asana Example: Tadasana (Mountain Pose) or holding another pose for some time without changing body position

- What is meant by the agonist and antagonist relationship? What is an example?

- When one muscle contracts, another muscle stretches.

- Flexing the elbow (to draw forearm up) contracts the bicep (called the agonist) and stretches the tricep (called the antagonist).

- What is reciprocal inhibition and how can you use this knowledge in practice?

- Reciprocal inhibition is an unconscious spinal reflex that causes the antagonist muscle to relax when the agonist muscle contracts.

- We can consciously access this reflex to deepen stretches by first holding a mild stretch until the body has acclimated and then engaging the opposing muscle to go deeper.

Joint Movements & Mobility

Answer Key

- Define Range of Motion (ROM)

- Range of motion (ROM) refers to mobility of each joint through its various directions of movement.

- Who uses ROM standards, and why?

- Specialists in orthopedics, physical therapy and related fields often utilize standards that define normal range of motion.

- The “standards” differ somewhat according to source.

- The intention is to define an ideal range in which movement maintains the flow of synovial fluid (which lubricates the joints) and promotes strength and flexibility of the related muscles.

- How are joints affected by over-stretching?

- When healthy ROM is exceeded, “the joint becomes hyperextended, less stable and potentially more vulnerable to injury.” (Mukunda Stiles)

- What are the effects of diminished ROM?

- When inactivity or poor posture causes diminished ROM, “the resulting rigidity in the joints and… muscles supporting it places more stress on neighboring joints and muscles.” (Mukunda Stiles)

- Why is joint mobility important in asana practice?

- An objective for asana is to move joints through their range of motion, thereby lubricating the joints as well as developing and maintaining strength and flexibility of muscles around the joint.

- Name and describe the movements of each of these joints: ankles, knees, hips, spine, wrists, elbows, shoulders, scapula and neck.

Ankles

- Plantarflexion – pointing toes

- Dorsiflexion – drawing toes back toward knee

- Eversion – outer edge of foot draws toward head

- Inversion – inner edge of foot draws toward head

- Rotation – circling of ankles

Knees

- Flexion – bending knee

- Extension – straightening knee

- Rotation (During Flexion) – while sitting in chair with feet under knees, turning foot outward and inward

Hips

- External Rotation – outward rotation of thighbone within hip socket

- Internal Rotation – inward rotation of thigh; comes from glutes

- Extension – from hands and knees, back of leg rises toward sky

- Flexion – from hands and knees, round to take knee to nose

- Adduction – draw leg across centerline of body

- Abduction – take leg out away from midline of body

Spine

- Forward bend

- Backbend

- Side bend to the left

- Side bend to the right

- Twist to the left

- Twist to the right

Wrists

- Flexion – take palm toward body

- Extension – make the stop motion with hand

- Radial deviation – from straight wrist, palm up, turn thumb side toward torso

- Ulnar deviation – from straight wrist, palm up, turn pinky side toward torso

- Rotation – circle wrists

Elbows

- Extension – straighten arms

- Flexion – bend arms

Shoulders

- Abduction – lift arms out to side

- Adduction – hands to shoulders, draw elbows toward one another

- External Rotation – “goal post” arms, palms facing forward

- Internal Rotation – “goal post” arms, rotate palms down to face back

- Flexion – raise arms upward

- Extension – draw arms back behind body

Scapula

- Adduction – squeeze shoulder blades

- Abduction – round thoracic spine

Neck

- Extension – drop head back

- Flexion – take chin to chest

- Lateral flexion both directions – draw ear toward shoulder

- Lateral rotation both directions – turn chin toward shoulder

- What are the established normal ranges of motion for each joint movement?

The following range of motion norms are from Structural Yoga Therapy.

Ankles

- Ankle Dorsiflexion 20° — Plantarflexion 50°

- Ankle Eversion 20° — Ankle Inversion 45°

- Ankle Rotation — combines previous motions

Knees

- Knee Extension 180° — Knee Flexion 150°

Hips

- Hip External Rotation 45-60° — Hip Internal Rotation 35°

- Hip Extension 30° — Hip Flexion 135°

- Hip Adduction 30-40° — Hip Abduction 45°

Spine

- Spine Extension – No standard; “from a yogic point of view, we look for symmetry and fullness in backbending and for a lengthening of the spinal column”

- Spine Flexion — No standard; “A yogic view is that, if the tone of the spine flexors is balanced to the opposing muscles, the erector spinae, the spine arcs evenly, creating a symmetrical semicircle.”

- Spine Lateral Flexion not established (“though it appears to be 45°”)

- Spine Rotation not established (“shoulder girdle 45°”)

Wrists

- Wrist Flexion 90° — Wrist Extension 80°

- Radial Deviation 20° — Ulnar Deviation 30°

- Wrist Rotation – combination of four preceding motions

Elbows

- Elbow Extension 0° (straight line) — Elbow Flexion 145°

Shoulders

- Shoulder Abduction 40° — Shoulder adduction 130°

- Shoulder External Rotation 90° — Shoulder internal rotation 80°

- Shoulder Flexion 180° — Shoulder Extension 50°

- Scapula Adduction not established — Scapula Abduction not established

Neck

- Neck Extension 55° — Neck Flexion 45°

- Neck Lateral Flexion 45° — Neck Lateral Rotation 70°

Muscle Pairs & Pose Examples

Answer Key

Part 1: For each movement type, select the key muscles involved:

| ELBOW FLEXION & EXTENSION | (1) | 🡪 | (C) | biceps & triceps |

| SHOULDER FLEXION & EXTENSION | (2) | 🡪 | ( I ) | anterior deltoid & posterior deltoid |

| SHOULDER ABDUCTION & ADDUCTION | (3) | 🡪 | (E) | middle deltoid & latissimus dorsi |

| SHOULDER ROTATION | (4) | 🡪 | (H) | subscapularis + teres major & infraspinatus + teres minor |

| SPINAL FLEXION & EXTENSION | (5) | 🡪 | (D) | rectus abdominis & erector spinae |

| HIP FLEXION & EXTENSION | (6) | 🡪 | (J) | iliopsoas & gluteus maximus |

| HIP ABDUCTION & ADDUCTION | (7) | 🡪 | (G) | gluteus medius + minimus & adductors |

| HIP ROTATION | (8) | 🡪 | (K) | gluteus medius + minimus & gluteus maximus |

| KNEE FLEXION & EXTENSION | (9) | 🡪 | (B) | hamstrings & quadriceps |

| ANKLE DORSIFLEXION & PLANTARFLEXION | (10) | 🡪 | (A) | tibialis anterior & gastrocnemius + soleus |

| WRIST FLEXION & EXTENSION | (11) | 🡪 | (F) | wrist flexor & wrist extensor |

Part 2: For each movement, name the prime mover (agonist) and antagonist muscles and provide an example of a pose or activity that uses the movement:

| Elbow flexion | Prime Mover – bicepsAntagonist – tricepsGarudasana, Sarvangasana |

| Elbow extension | Prime Mover – tricepsAntagonist – bicepsUtkatasana, Purvottanasana |

| Shoulder flexion | Prime Mover – anterior deltoidAntagonist – posterior deltoidAdho Mukha Vrksasana, Dolphin Pose |

| Shoulder extension | Prime Mover – posterior deltoidAntagonist – anterior deltoidVirabhadrasana, Halasana |

| Shoulder abduction | Prime Mover – Middle DeltoidAntagonist – Latissimus DorsiPrasarita Twist, Trikonasana |

| Shoulder adduction | Prime Mover – Latissimus DorsiAntagonist – Middle DeltoidGarudasana, Thread the Needle |

| Shoulder (internal) medial rotation | Prime Mover – Subscapularis + Teres MajorAntagonist – Infraspinatus & Teres MinorReverse Namaste, Open Sesame |

| Shoulder (external) lateral rotation | Prime Mover – Infraspinatus + Teres Minor Antagonist – Subscapularis & Teres MajorTadasana (arms rotate out), “Goal Post” Arms |

| Spinal flexion | Prime Mover – Rectus AbdominisAntagonist – Erector SpinaeSeated Cat Cow, Bakasana |

| Spinal extension | Prime Mover – Erector SpinaeAntagonist – Rectus AbdominusMatsyasana, Standing Backbend |

| Hip flexion | Prime Mover – IliopsoasAntagonist – Gluteus MaximusPaschimottanasana, Prasarita Padottanasana |

| Hip extension | Prime Mover – Gluteus MaximusAntagonist – IliopsoasBalancing Table, Salabhasana |

| Hip abduction | Prime Mover – Gluteus Medius + MinimusAntagonist – AdductorsUpavistha Konasana, Malasana |

| Hip adduction | Prime Mover – AdductorsAntagonist – Gluteus Medius + MinimusGomukhasana, Ardha Matsyendrasana |

| Hip (internal) medial rotation | Prime Mover – Gluteus Medius + MinimusAntagonist – Gluteus MaximusParsvottanasana BACK HIP, Yin Yoga Deer Pose |

| Hip (external) lateral rotation | Prime Mover – Gluteus MaximusAntagonist – Gluteus Medius + MinimusEye of the Needle, Agnistambhasana |

| Knee flexion | Prime Mover – HamstringsAntagonist – QuadricepsLunges, Virabhadrasana 2 |

| Knee extension | Prime Mover – QuadricepsAntagonist – HamstringsVirabhadrasana 3, Ubhaya Padangusthasana |

| Ankle dorsiflexion | Prime Mover – Tibialis AnteriorAntagonist – Gastrocnemius + SoleusSupta Padangusthasana, Utthita Hasta Padangusthasana |

| Ankle plantarflexion | Prime Mover – Gastrocnemius + SoleusAntagonist – Tibialis AnteriorUrdhva Mukha Svanasana, Virasana |

| Wrist flexion | Prime Mover – Wrist FlexorAntagonist – Wrist ExtensorWrist Stretches, Padahastasana |

| Wrist extension | Prime Mover – Wrist ExtensorAntagonist – Wrist FlexorAdho Mukha Svanasana, Arm Balances |

Part 3: Teaching Applications

- How can teaching awareness of these muscle pairings impact students?

- Being aware of the muscle pairs involved in actions can help a student to deepen her experience of a posture with conscious focus. For example, when the student wishes to lengthen the hamstrings, she can actively engage the quadriceps muscles.

- Reciprocal inhibition is an unconscious spinal reflex that causes the antagonist muscle to relax when the agonist muscle contracts. This reflex can be consciously accessed to deepen stretches by first holding a mild stretch until the body has acclimated and then engaging the opposing muscle to go deeper.

- See also: Active Stretching in Flexibility & Stretching.

- Provide examples of how knowledge of the muscle relationships can inform sequencing and class planning.

- This key relationship among muscles for movement can guide the intention you set to address an anatomical area.

- For example, as shown in the Yoga International video, Asana Anatomy: Trapezius and Serratus Anterior, if you are considering an approach for rounded shoulders, the muscle pair would be the middle trapezius (middle of shoulder blades) and serratus anterior (side ribs, responsible for pulling scapula forward). In the video, yoga teacher Sarah Guglielmi shows practices for releasing tension in the serratus anterior and learning how to strengthen through the trapezius.

- Avoid choosing too many poses that use similar muscular actions.

- Olga Kabel offers these considerations when targeting a specific body area:

- Identify target parts of skeleton.

- Determine the target muscles and the muscle actions; in order to provide integration, plan to involve a more general area of the body—not just the specific muscles.

- Identify poses and pose adaptations that will stretch and strengthen those muscles.

- Contract muscles first; then relax them; then stretch them.

- Take breaks to feel effect of practice on target area.

Hyperextension & Hypermobility

Answer Key

- Describe a healthy musculoskeletal system and the effects of optimally functioning joints.

Health of the musculoskeletal system displays as a balance in stability and mobility. When joints are functioning optimally, moving through their healthy range of motion, they are, of course, helping us to move pain-free with fluidity and grace, power and strength. But there is more going on in the body than we can see and even feel. As Ray Long MD explains here, in addition to their more obvious functions, healthy synovial joints also secrete a fluid that:

- Lubricates the joint surfaces, reducing friction during movement and acting as a shock absorber through fluid pressurization

- Carries oxygen and nutrients to the cartilage

- Removes carbon dioxide

- List potential issues related to musculoskeletal health.

Musculoskeletal issues include:

- Pain

- Postural issues

- An imbalance in mobility and stability of joints (in general)

- Hypermobility (specifically) which is associated with an increased incidence of musculoskeletal injuries (Ray Long MD)

While a few joints in the body are immovable or slightly movable, most of the joints are “freely movable” and have elaborate structures. Their complexity is one reason they’re particularly vulnerable to injury. A joint is only as healthy as the muscles surrounding it. Relaxed, flexible muscles lead to a more mobile joint. – Larry Payne

- Describe potential consequences of diminished mobility.

When inactivity or poor posture causes diminished range of motion, “the resulting rigidity in the joints and… muscles supporting it places more stress on neighboring joints and muscles.” (Mukunda Stiles)

- Describe potential consequences of excessive mobility.

When healthy range of motion is exceeded, “the joint becomes hyperextended, less stable and potentially more vulnerable to injury.” (Mukunda Stiles) Healthy ROM may be exceeded by:

- Overstretching

- Postural issues

- Injury

- Skeletal issues

- Joint hypermobility (see below)

- Discuss how hypermobility may be misunderstood as “being good at yoga.”

I had a student in one of my classes who was hypermobile, and I often caught my other students asking her how she got so good at yoga — there’s just a sense that more flexible is better when it comes to yoga. Unfortunately, hypermobility is a real problem that can lead to joint instability, chronic pain, and sometimes even costly and painful joint repairs. – Bridget Frederick

- Describe the ways in which yoga practice is a powerful tool for optimizing musculoskeletal balance.

Yoga practice can be an excellent tool for balancing mobility and strength, particularly when used to meet these objectives:

- Maintain or regain joint range of motion.

- Strengthen the muscular stabilizers of the joints.

- Comment on using asana to move joints through their healthy range of motion.

An objective with asana is to move the joints through their healthy range of motion, thereby lubricating the joints as well as developing and maintaining strength and flexibility of muscles around the joint.

- Provide general considerations to keep in mind to optimize joint health.

- Keep in mind the philosophy and value of sthira sukham asanam / right effort.

- Become aware of activities that cause pain and avoid them or reduce intensity according to symptoms.

- Don’t push into end ranges of motion. Ease into them. “Joints adapt to gradual changes much better than abrupt or rapid ones. For example, I deliberately slow down my movement as I near the end point of forward flexion in Uttanasana.” (Ray Long MD)

- Gently engage the muscles that stabilize joints, especially when moving toward end points of mobility ranges. “This is a cornerstone of rehabilitation and injury prevention. Knowledge of the musculoskeletal system and visualization helps in this process.” (Ray Long MD)

- Provide general asana practice techniques that can help to optimize joint health with all students.

- Align bones and engage muscles.

- Re-set neurological (proprioceptive) normal.

- Describe hyperextension.

When a joint is hyperextended, the joint range in extension is greater than average, causing bones to be out of alignment. In asana practice, this “misdirects the forces that create the form of the asana” (Ray Long MD)

In people with hyperextension of the knees, when their knees are straight, instead of the thigh bones on top and the shinbones on bottom forming one straight line, your knee joints bow slightly backwards. In addition, when your knees are hyperextended, your kneecaps don’t face straightforward; instead, they turn in slightly… The problem with this structural condition is that you tend to bear more weight on your heels than on the balls of your feet and your thighs are not directly aligned with your shins. You can see this in this photo of me from several years ago.– Nina Zolotow

- Provide examples of addressing hyperextension.

If there is a tendency to hyperextend the knees in standing poses, the simplest action may be to create a slight bend in them. However, Nina Zolotow teaches a better way for guiding the student in learning to engage stabilization muscles and to align the bones:

- Bend knees and move shins forward, shifting some weight from the heels to the balls of the feet.

- Straighten knees by lifting thighs. Keep some weight in the balls of the feet.

Alternatively, she suggests, you can “try softening your front thigh muscles and allow your thighbone to move slightly forward so it aligns more directly over your shinbone and more weight moves onto the ball of your foot.”

For more guidance on engaging muscles around joints and counteracting hyperextension in more poses, see:

- Define joint hypermobility and discuss considerations regarding the number of hypermobile joints a person has.

Joint hypermobility is also known as “generalized ligamentous laxity.” It refers to a laxness (looseness) in the ligaments that stabilize joints.

- This laxity can range from mild “loose joints” and “double jointedness” to systemic pathological conditions.

- The degree of hypermobility can be measured using the Beighton criteria, which examines factors such as knee, elbow and thumb hyperextension.

- “It is fairly common for many people to have one or two joints that are more mobile than average, or hyperflexible. For these people, they might want to take care not to overstretch their hyperflexible joints (see my yoga recommendations below). However, if you have more than two hypermobile joints… [you could have] joint hypermobility syndrome, a commonly overlooked cause of chronic pain.” (Baxter Bell MD)

- Describe the felt sense of being in a hypermobile body.

I’m going to share my own experience from the perspective of a practitioner who definitely has hypermobile joints. In my body, there was a time when it felt like everything moved whether I wanted it to or not. I lost track of the number of times that I twisted an ankle as a kid. My shoulder joints felt as if they could be pulled right out of their sockets if I allowed them to. And my sacrum intermittently has the feeling of popping in and out of place. That is the felt sense of moving around with hypermobility. Through many years of practicing Ashtanga vinyasa yoga and through trial and some error in my own body (as well as with the guidance and suggestions of a great teacher!) I have found what works for me. If your body does not fit in the middle of the bell curve, then the common ways of doing poses, common alignment cues, etc. might not apply in the same way to you. – Christine, Yoganatomy.com

- Discuss teaching considerations and techniques for students with hypermobile joints.

In the case of joint hypermobility, consider these suggestions:

- Address Hyperextension — See hyperextension.

- Focus on Stabilization in Asana Practice — With each pose you teach, help students prioritize stabilization, not just mobility. “People with joint hypermobility… have to work extra hard to stabilize their joints.” (Sarah Warren St. Pierre) See core strengthening fundamental teachings for help in understanding how the deep stabilizers function, and teaching related concepts.

- Build Strength in General — Consistently engage in strengthening practices.

- Pay Particular Attention to Strengthening Joint Stabilizers — “Put more time and effort into [bodily strength that] works to stabilize the joints… Support your mobility by exploring your connection to [your core and TA, pelvic floor and psoas.] Around the shoulder girdle, make friends with your serratus anterior.” (Yoganatomy.com)

- Approach Stretching with Caution & Use Specific Techniques — See info on various ways for students with hypermobile joints to approach stretching.

- Consciously Retrain the Mindbody — Use proprioception practices and neurological techniques to retrain the mindbody to instinctively recognize healthy movement patterns. See below for Re-Setting Normal with Proprioception, plus consider other yoga therapy techniques and/or somatics as Sarah Warren St. Pierre notes here. Please also note, as Leslie Kaminoff insightfully shares here, setting a boundary that the body doesn’t automatically know is there can be both physically and emotionally challenging.

- Pay Attention to Fatigue — “Stopping when your muscles feel fatigued is especially important in a hypermobile body. You don’t have tightness around the joints to keep the tendons, ligaments, and other structures from getting over-stretched. You have to stop yourself.” (Yoganatomy.com)

- Describe ways to teach students with hypermobility how to stretch in ways to avoid excessive joint movement.

- “Critically evaluate how things feel in your own body. For example, does that cue to line up the feet in warrior pose feel okay? It might be just fine or it might send pressure into the SI joints. Check into your body and adjust for what you feel.” (Yoganatomy.com)

- Avoid going to maximum range of motion with hypermobile joints. Use props or otherwise instruct students to go only to 75-80% of their max.

- When a hypermobile student has tight muscles, “look for sensation of stretch in the center of the muscle body and not near the joints, and become familiar enough with ‘normal’ joint movement [to be able to] visually check to make sure they are not going beyond it.” (Baxter Bell MD)

- “Another way to avoid excessive joint movement is to isometrically contract the muscles around a very mobile joint before you head into a deeper range of motion and maintain that contraction while you are in the pose. This will both stabilize the joint more and decrease the range of motion through which you can move it.” (Baxter Bell MD)

Spinal Regions & Vertebrae

Answer Key

Vocabulary Mix & Match

| BACKBONE (1) | 🡪 | ( C ) | Another name for the spine |

| CERVICAL SPINE (2) | 🡪 | ( G ) | Top region of the spine, labeled C1-C7 |

| COCCYX (3) | 🡪 | ( K ) | Three to five fused vertebrae with a tip that typically points straight down |

| LUMBAR SPINE (4) | 🡪 | ( H ) | Low back region of the spine, labeled L1-L5 |

| NORMAL CURVES (5) | 🡪 | ( B ) | A term used by anatomists to underscore the importance of the four spinal curves |

| SACRUM (6) | 🡪 | ( E ) | Five fused vertebrae that make up the base of the spine and the back of the pelvis |

| SPINAL COLUMN (7) | 🡪 | ( A ) | Another name for the spine |

| SPINE (8) | 🡪 | ( I ) | Made up of 33 specialized bones called vertebrae, houses the spinal cord which provides communication between brain and body |

| SPINOUS PROCESSES (9) | 🡪 | ( L ) | The bony projections from the vertebra that you can feel when you palpate your spine; they provide attachment points for muscles and ligaments |

| THORACIC SPINE (10) | 🡪 | ( J ) | Middle region of the spine, labeled T1-T12 |

| VERTEBRAE (11) | 🡪 | ( D ) | Plural of “vertebra,” specialized bones that make up the spine |

| VERTEBRAL COLUMN (12) | 🡪 | ( F ) | Another name for the spine |

- What are some other names for the spine?

- The spine is also known as the spinal column, vertebral column or the backbone.

- What regions make up the spinal column? How many vertebrae are in each region? Which are fused?

- Cervical Spine: 7 vertebrae

- Thoracic Spine: 12 vertebrae

- Lumbar Spine: 5 vertebrae

- Sacrum: 5 fused vertebrae

- Coccyx: 3 to 5 fused vertebrae

- How are vertebrae labeled/numbered?

- The vertebrae are numbered from the top down: C1 to C7, T1 to T12, L1 to L5, and S1 to S5.

- Where do we experience the most movement in the spine, and why?

- The junctions where the curves of the spine change direction allow the most movement: C7 – T1, T12 – L1, and L5 – S1.

- For this reason, these points of transition are the most vulnerable to injury.

- What is the shape of each curve?

- Cervical Spine – Lordotic: convex, curving in toward body

- Thoracic Spine – Kyphotic: curves away from body

- Lumbar Spine – Lordotic: convex, curving in toward body

- Sacrum – Kyphotic: curves away from body

- What is the sacrum?

- The sacrum is made up of 5 fused vertebrae.

- It is the base of the spine and the back of the pelvis.

- What are the “primary curves” and why are they given that name?

- The thoracic and sacral curves — the kyphotic spinal curves — are developed in utero, and are therefore called primary curves.

- What are the “secondary curves” and why are they given that name?

- The cervical and lumbar curves develop later and are thus called secondary curves.

- How can Savasana be used to identify spinal curves?

From Savasana, notice the parts of the spine that are in contact with the earth.

These are the kyphotic curves:

- Upper back

- Sacrum

Then take note of the parts of the spine that are off the floor. These are the lordotic curves:

- Neck

- Low back

- What are vertebrae?

- The spine is made up of 33 irregular, specialized bones called vertebrae.

- The vertebrae vary in size and shape according to their location and associated function but follow a similar structural pattern.

- Describe the general structure of an individual vertebra.

- Each vertebra is labeled as having a “body” or “centrum” which is the thick oval bone forming the front of the vertebra.

- The “vertebral arch” is the name for the posterior portion of each vertebra.

- The opening in the vertebra for the spinal cord is called the “vertebral foramen.” (“Foramen” means a natural opening or passage, especially through a bone.)

- There is another opening called the “intervertebral foramen” which is the passage for the spinal nerve to exit the from the vertebral column.

- The bony projections from the vertebra are called “spinous processes.” They provide attachment points for muscles and ligaments. (The atlas and coccygeal vertebrae do not have spinous processes.)

- Spinous processes are the ridges that can be felt along the back of the spine.

- What are intervertebral discs?

- Each moveable segment of the vertebral column (except C1/C2) is separated by “intervertebral discs” and “articulating facet joints.”

- Discs are spongy material that serve to absorb shock.

- “The intervertebral discs are fibrocartilaginous cushions serving as the spine’s shock absorbing system, which protect the vertebrae, brain, and other structures (i.e. nerves).” (source)

Back Muscles

Answer Key

- Describe two ways that back muscles may be categorized.

- Back muscles may be categorized as superficial, intermediate or deep.

- Another common categorization is extrinsic vs. intrinsic. In this system, extrinsic muscles encompass the superficial and intermediate muscles and intrinsic refers to the deep back muscles.

- List the muscles in each category and their primary association.

- Superficial Muscles — trapezius, latissimus dorsi, levator scapulae, rhomboids — associated with shoulder movement

- Intermediate Muscles — serratus posterior superior, serratus posterior inferior — associated with movement of the rib cage

- Deep or Intrinsic Muscles — erector spinae, quadratus lumborum (QL), multifidus — considered part of the core musculature, associated with stabilizing and moving spine

- Where are superficial back muscles located? What actions are associated with them, and what asanas strengthen and stretch them?

- These muscles are located just underneath the skin and superficial fascia. They originate from the spinal column and attach to shoulder bones

- They are associated with movements of the shoulder.

- Adho Mukha Svanasana strengthens the lats and Garudasana arms stretch them.

- Where are intermediate back muscles located? What do they do, and what asanas stretch and strengthen them?

- The serratus posterior muscles run from the spinal column to the rib cage.

- They assist with movements of the rib cage.

- Janu Sirsasana and Parivrtta Janu Sirsasana stretch the serratus posterior superior muscle and Plank Pose strengthens it.

- Where are the deep back muscles located? What actions are they responsible for?

- The deep back muscles are covered by deep fascia.

- These muscles are associated with movements of the spine and in controlling posture.

- What is the relationship between deep back muscles and the core?

- The deep back muscles are considered part of the core.

- Describe the erector spinae and their functions.

- The erectors are deep, located beneath two other layers of muscles and covered by fascia.

- The erectors consist of three groups of muscles running the length of either side of the spine.

Functions:

- Help to maintain erect posture.

- Stabilize the spine during flexion.

- Assist in side-bending and spinal rotation.

- Provide asana examples for strengthening and stretching the erector spinae.

- The backbend salabhasana strengthens the erector spinae.

- The forward bend paschimottanasana stretches the erector spinae

- Describe the quadratus lumborum (QL) and its functions.

- The QLs are located on either side of the lumbar spine, between the pelvis and the lowest ribs.

- They may also be considered the deepest abdominal muscles.

- These muscles are involved in movement and stabilization of the lumbar spine and pelvis. Because of its connection to the 12th rib, it’s also involved in breathing.

- Discuss potential issues with the QL and a type of strengthening that can help support it.

- “Its many functions and constant daily use make the quadratus lumborum muscle an important one to consider. (source)

- “When your back muscles are weak or you have poor posture… QLs, work overtime to stabilize your spine and pelvis, leaving them tight and sore. These deep muscles are also near critical organs like the kidneys and colon, which means that in addition to contributing to an achy back they can adversely affect your digestive health, and therefore energy and well-being.” (source)

- See QL stretches here and poses for QL strengthening here.

- “Core and lower back strengthening can help support the QL so it is not overworked and strained unnecessarily… Deep, intentional breathing can also help to relax an overactive muscle, as well.” (source)

- What do multifidus muscles do and how can knowledge of them help students?

- The multifidus muscles are a series of deep muscles that run the length of the spine.

- They stabilize vertebrae as well as assist in spinal rotation and extension.

- With those who have experienced back pain, knowledge of the multifidus muscles can be helpful in learning to recruit the core for stabilization.

Spinal Functions

Answer Key

- What are the functions of the spine?

- The spine houses the spinal cord which provides communication between brain and body.

- It transmits loads between the upper body and the lower body

- In what two complementary ways is the spine designed to function?

- The spine is designed for both movement and stability.

- Explain how the curves of the spine work.

- The curves of the spine work like a coiled spring and provide balance, flexibility, stress absorption and distribution of energy.

- What are the attributes of a healthy spine?

- The spine is designed for movement and for stability, and a healthy spine demonstrates these attributes.

- What is the function of the spinal cord? Provide a metaphor to describe it.

- The spinal cord extends from the brain stem to the lower back, relaying information to and from the brain via 31 pairs of spinal nerves that connect the spinal cord to the rest of the body.

- It can be thought of like a switchboard operator.

The spinal cord works a bit like a telephone switchboard operator, helping the brain communicate with different parts of the body, and vice versa. Its three major roles are:

- To relay messages from the brain to different parts of the body (usually a muscle) in order to perform an action

- To pass along messages from sensory receptors (found all over the body) to the brain

- To coordinate reflexes (quick responses to outside stimuli) that don’t go through the brain and are managed by the spinal cord alone

– Study.com

- Give examples of areas of the body supplied by the nerves in the spine, and potential conditions associated with nervous system issues.

- Nerves in the cervical spine supply blood to the head, pituitary gland, the brain, and sympathetic nervous system among other areas. Issues may relate to headaches, chronic tiredness and more.

- Nerves in the lumbar spine communicate with the intestines, lymph circulation, lower legs, hip bones and rectum among other areas. Issues may relate to digestive issues, varicose veins, backaches and more.

Spinal Movements

Answer Key

- What are the six directions of spinal movement?

- Forward Bend

- Backbend

- Side Bend Left

- Side Bend Right

- Twist Left

- Twist Right

- What two additional types of spinal movement are we concerned with in yoga?

- Spinal or Axial Extension / Elongation

- Inversion

- Give an asana example for each of the types of spinal movement.

- Forward Bend: Uttanasana (Standing Forward Bend)

- Backbend: Bhujangasana (Cobra Pose)

- Side Bend: Parighasana (Gate Pose)

- Twist: Ardha Matsyendrasana (Half Lord of the Fishes Pose)

- Spinal Extension: Urdhva Hastasana (Upward Salute)

- Inversion: Salamba Sarvangasana (Supported Shoulderstand)

- What is the objective of spinal / axial extension poses?

- The objective of spinal extension poses is to create space between the vertebrae, thus lengthening the spine.

- What is compression and when is it usually desirable?

- Compression refers to drawing the bones closer together.

- Compression is desirable therapeutically; extension is the typical purpose of asana.

- What are some teaching considerations related to spinal alignment in forward bends?

- In seated forward bends, a fundamental starting point is sitting upright as opposed to sitting back on the sit bones.

- Assess student in Dandasana (Staff Pose). Is she able to attain pelvic neutrality with the sacrum tilted slightly forward?

- Consciously lengthen the spine to maintain natural curves of the spine.

- Internally rotate the thighs.

- Experts typically advise that forward bends begin with an anterior tilt of the pelvis but to then allow the pelvis to move into posterior tilt.

- What are some teaching considerations related to spinal alignment in backbends?

- When there is tightness in the upper back, the more flexible parts of the spine (the neck and low back) may compensate. Watch out for straining in the neck or overarching in the low back.

- Expert Doug Keller explains that in Tadasana (Mountain Pose), the pelvis is unmoving and to keep it stable, we may “slightly scoop the tailbone down and forward,” resulting in the sacrum being in counternutation. He explains counternutation doesn’t apply during backbending and forward bending.

- In backbending, the tailbone lifts (called “nutation”) as a result of the top of the sacrum moving into the body. “Tucking” the tailbone is the opposite of this action and therefore makes backbending more difficult. Instead, if nutation is allowed to happen naturally, backbends feel better. For much more on the topic of “tucking” or “scooping” the tailbone, see Alignment Cueing: The Spine.

- What are some teaching considerations related to spinal alignment in lateral bends?

- Expert Julie Gudmestad points out that some seated side bends such Parivrtta Janu Sirsasana (Revolved Head-to-Knee Pose) and Parivrtta Upavistha Konasana (Revolved Wide-Angle Seated Forward Bend) may put beginners and “stiffer students” at risk of straining their low backs. As a result, she recommends working first with side bends over a stack of blankets and with poses that improve adductor and hamstring flexibility in safer poses such as Supta Padangusthasana (Reclined Hand to Toe).

- What are some teaching considerations related to spinal alignment in twists?

- Twisting can be one of the major culprits of sacroiliac (SI) joint pain. Many experts now advise that students always move the pelvis and sacrum together. In twisting, this means allowing the pelvis to move with the sacrum to accommodate spinal rotation rather than anchoring it while moving the spine independently.

- Keeping the spine long distributes the forces in the disks evenly.

- Depth in twisting is achieved by length.

- There is a tendency to avoid twisting where flexibility is limited (such as in the thoracic spine) and to overwork areas that twist more easily (such as the neck).

- Avoid initiating a twist from the head and neck and instead twist from the core, using abdominal and back muscles to turn the entire rib cage. Let the head and neck follow.

- What are some teaching considerations related to spinal extension?

- “Spinal or Axial Extension” in yoga typically refers to reducing the spinal curves or lengthening the entire spine.

- The objective is to create space between the vertebrae, thus lengthening the spine.

- Spinal extension refers to the relationship of the spinal curves to each other while the phrases “forward bending” and “backbending” refer to particular movements through space.

- From the “root” comes the “rise” which refers to pressing into the earth and noticing how this activation causes a rebounding or lifting effect.

- Once the foundation is set, potential teaching cues might include, “Lengthen (or elongate) the spine” or “Extend the spine” or “Feel a lifting through the top of the head.”

- What are some teaching considerations related to spinal alignment in inversions?

- In Headstand and Shoulderstand there is particular risk, of course, to the neck.

- Headstand and Shoulderstand may be accessible to some students before they are physically ready to practice them. That is, a student may be able to force herself into Headstand, for example, and then to hold the pose longer than she is safely prepared for.

- Teaching inversions requires determining readiness, providing appropriate preparation and teaching alternatives.

Healthy Posture Answer Key Vocabulary Mix & Match

| ANATOMICAL POSITION | ( 1 ) | 🡪 | ( C ) | In humans, defined as “standing up straight with the body at rest” |

| HEALTHY POSTURE | ( 2 ) | 🡪 | ( D ) | A natural bearing of the body that includes a comfortably neutral spine and promotes healthy internal functioning and muscular efficiency |

| ISCHEMIA | ( 3 ) | 🡪 | ( H ) | Insufficient supply of blood to an organ; As it relates to posture, refers to the compression of blood vessels resulting from chronic muscular tension, causing pain and damage |

| MUSCLE MEMORY | ( 4 ) | 🡪 | ( A ) | Movement or posture that has become automatic; a result of the nervous system shifting control and memory of a repeated pattern from areas of the brain responsible for making voluntary decisions to making them subconscious |

| NEUTRAL PELVIS | ( 5 ) | 🡪 | ( J ) | A state of equal hip height, a neutral pelvic tilt, a neutral front-to-back placement and the pelvis is pointing straight ahead |

| NEUTRAL SPINE | ( 6 ) | 🡪 | ( F ) | A state in which the spinal curves are not too much or too little for the individual’s healthy norm |

| POSTURE | ( 7 ) | 🡪 | ( B ) | A collection of (typically unconscious) habits and holding patterns (which form our muscle memory) that create “an attitude of the body” or an “orientation to the present moment” which reinforces itself through bodily structures and physiology |

| SENSORY MOTOR AMNESIA | ( 8 ) | 🡪 | ( I ) | The natural way in which bodily movement and posture becomes “automatic and involuntary” leading to loss of sensation, a lack of awareness of the muscular pattern, and a temporary inability to relax tight muscles |

| STANDARD ANATOMICAL POSITION | ( 9 ) | 🡪 | ( G ) | Standing up straight and facing forward with the arms by the sides and palms facing forward |

| STANDING IN NEUTRAL | ( 10 ) | 🡪 | ( E ) | Another way to describe anatomical position; refers to standing with the bones stacked vertically and the two sides of the body displaying symmetry |

- Define posture.

Drawing from the teachings of many sources, we can define posture as a collection of (typically unconscious) habits and holding patterns (which form our muscle memory) that create “an attitude of the body” or an “orientation to the present moment” which reinforces itself through bodily structures and physiology.

Posture… You know it’s distinctive – you can easily and immediately recognize close friends just by how they move and how they hold their collection of arms, legs, torso, and head together – that configuration is as individual to them as their fingerprint. But is posture JUST a description of how someone stands and moves – just a math equation of angles, force, and mass? Or does it go deeper than that?.Mary Bond, author of The New Rules of Posture … says that posture is our “orientation to the present moment.” It’s affected not only by our bones, muscles, and fascia, but by our thoughts, emotions, traumas, history, chemistry, family, work – by all those holding patterns developed over years of living and being on this gravity-endowed planet. – Heather Longoria

- Discuss how posture manifests.

- YogaUOnline explains here that posture is the result of physical exploration that began when we were babies, evolving into habits that we engage in repetitively, becoming “written into the brain” and ever “more ingrained.”

- Through the evolution of habit, the body itself begins to “adapt to hold that posture.”

- As a result, our habits become embedded into our bodily structure which continues to recreate and reinforce itself via our muscular holding and breathing patterns, fascia, nervous system, and mental states.

If there’s one thing that everyone from bestselling authors to renowned philosophers agree on, it’s the power of habits… Small actions, repeated until we do them almost unconsciously, shape our lives. What’s less universally acknowledged is that our posture is a collection of habits, almost always deeply unconscious. Like the habits of thought that shape our lives, our postural habits shape our spines. – Eve Johnson

- Is posture genetic?

While many sources continue to propagate the medical system’s myth that genes can “cause” conditions, the 2003 Human Genome Project provided irrefutable proof that genetic determinism is false. To believe that one has “bad genes” can cause severe harm through its built-in victimization mindset. (See more here in “Where Mainstream Medicine Got it Wrong.”)

In reality, we all have predispositions but also tremendous control over the factors that impact our well-being. Eve Johnson explains this from her experience:

I learned that posture is cultural, and that although every woman in my family had a rounded upper back, our genes weren’t the problem. Like all little girls, we had modeled our posture on our mother’s, and achieved the same results. – Eve Johnson

AN EXAMPLE OF HEALTHY POSTURE BUILT INTO CULTURAL NORMS & HABITS

[I was on a] train from Lyon to Aix en Provence. At one of the stops along the way, a tall black woman, Muslim by her clothing, stopped by our seats to get her suitcase from the rack above our heads. The suitcase was huge. For a moment, I struggled to form the French words for “my husband would be happy to help you with that.” (It’s true, he would have been). Before I could speak, she had lifted the suitcase from the rack. She centred it on her head for a moment, then lowered it to the floor and wheeled it away. I watched her graceful walk and her long, straight spine, until she disappeared. In its own way, this sight was as moving as Sainte Chapelle, and for some of the same reasons. I had just witnessed a posture as old as time, and as new as a toddler. Her strength had nothing to do with going to the gym, and everything to do with living in Original Alignment. This is our birthright as human beings, our first way of being in our bodies, and our chance to experience lifelong mobility, strength and relaxation. – Eve Johnson

- What criteria are often used when identifying healthy posture?

The identification of healthy posture often involves these criteria:

- A neutral spine

- A neutral pelvis

- Muscular balance

- Body symmetry – It’s common to find bodily symmetry as a stated factor in healthy posture and pose alignment. However, please review Body Symmetry vs. Balance below for important considerations.

- Why does healthy posture matter?

While posture may be discussed in terms of how it affects one’s appearance, here we focus on the impact that posture has on healthy functioning.

- Healthy posture promotes healthy internal functioning and muscular efficiency.

Fundamental to why yoga works is its use of breath practices and the overall effect on the nervous system and stress. The ability to breathe naturally without constriction is a key to promoting health. Poor posture, however, can lead to poor breathing.

Did you know that your ability to take a deep, full breath is influenced by your posture?… If the muscles that allow your rib cage to expand are tight — due to habitual slouching or other postural problems — your lungs won’t be able to expand to their maximum… And if some of your chest or back muscles are weak, your endurance will be affected… To maintain good posture for optimum respiration, cultivating both the flexibility and strength of your torso muscles is vital. – Nina Zolotow

- Describe a “neutral” spine.

- Since the spine is naturally curved, a neutral spine isn’t straight but is instead demonstrated when the curves are not too much or too little for the individual’s healthy norm.

- Biomechanics experts explain that a neutral spine is where it is “most relaxed.”

- Why may students find it difficult to identify a neutral spine?

- A person with chronically poor posture and the related muscular imbalances will typically have a difficult time, at first, in identifying this state. This is in part because the student may correlate what feels “comfortable” or “normal” with “relaxed” despite exhibiting poor posture and spinal stress. (Read more in Bernie Clark’s teaching below.)

When you stand in mountain pose (Tadasana), can you find the position for your spine that has the least amount of tension? If so, that is likely your neutral position. Unfortunately, chronically poor posture can also feel relaxed, but there may be a lot of stress seeping into the connective tissues because the muscles have lost their tone. When the muscles are weak, the fascia has to do the job of the muscles. When you pay attention to the tension in your spine, you need to notice not just muscular tension, but also the stresses in your joints and fascia… You may have to experiment—try different postures and check out how each position of your spine feels. Where do you feel free, light, long, yet relaxed? That is probably your neutral position. If this experimentation still doesn’t work, use a mirror or the eyes of a qualified teacher to help you discover your neutral spine. – Bernie Clark

- Describe four considerations for pelvic alignment in Tadasana (Mountain Pose).

Roger Cole describes these four aspects of pelvis and hip alignment in Tadasana:

- Equal Hip Height

- Neutral Pelvic Tilt

- Neutral Font-to-Back Placement

- Pelvis Pointing Straight Ahead

- While general symmetry is correlated with healthy posture, describe Jenni Rawlings case for focusing less on symmetry and more on balance.

- Typically, pose alignment includes finding symmetry between the two sides of the body.

- While general symmetry is correlated with healthy posture, Jenni Rawlings lays out the case here why idealizing symmetry is unsupported by research and by the body itself, which demonstrates asymmetry of the lungs and other internal organs.

Although an ideal of symmetry seems intuitively valuable in yoga, in reality no strong evidence exists to support this common belief. Countless scientific studies have drawn no link between body asymmetries and pain, dysfunction, and poor health… A look at the inner structure of our body [shows that we] are all asymmetrical on the inside… Our two lungs are innately different from one another in both size and structure… And whereas our heart sits to the left of center, our large liver sits to the right of center… Our diaphragm, our main muscle of respiration, is also asymmetrical! Scientific evidence simply does not support the belief that symmetrical alignment is more ideal than any other alignment… When we idealize the symmetry and “optimal alignment” of a pose like tadasana, we are comparing ourselves to the imaginary, symmetrical, vertically aligned person in the anatomy textbook drawing… simply one arbitrary position that is used as a reference point in the medical field. – Jenni Rawlings

- Instead of symmetry Rawlings proposes that the objective be balance.

Instead of emphasizing bodily symmetry, a more helpful concept for yoga teachers to focus on is balance… Whereas symmetry is the quality of sameness on both sides, balance is about steadiness of position — like the tree that has adapted to its environment and does not fall over. – Jenni Rawlings, Yoga International, The Myth of Symmetry in Yoga link

- What common lifestyle factor has a significant impact on posture and, therefore, healthy functioning?

- Sitting too much has a significant impact on posture.

Research indicates that on average, an American adult spends 10-12 hours each day sitting… More than 60 percent of people worldwide spend more than three hours a day sitting down, and the researchers calculated that sitting time contributed to some 433,000 deaths a year among 54 countries… Prolonged sitting affects the architecture of the spine, hips and neck as well putting the individual at risk for skeletal fractures. – Yoga for Healthy Aging

- Discuss the maintenance of healthy posture.

In addition to achieving healthy posture, equally challenging is learning to maintain it.

REQUIRES LEARNING NEW HABITS

I learned new habits: sitting with my weight as far toward my pubic bone as possible, turning my feet slightly out instead of keeping them parallel, releasing my chin, and elongating the back of my neck. More problematic, I had to unlearn habits, such as locking my knees when I stood and, most of all, lifting my chest… Over those two days, my new alignment began to feel right. – Eve Johnson

Postural Issues & Conditions

Answer Key

Vocabulary Mix & Match

| HYPERKYPHOSIS | ( 1 ) | 🡪 | ( D ) | Another name for kyphosis |

| HYPERLORDOSIS | ( 2 ) | 🡪 | ( F ) | Excessive inward curvature of the lumbar spine, causing a forward (anterior) pelvic tilt |

| KYPHOSIS | ( 3 ) | 🡪 | ( B ) | Excessive forward curvature of the thoracic spine (clinically defined as greater than 50 degrees) |

| LORDOSIS | ( 4 ) | 🡪 | ( E ) | Sometimes used for hyperlordosis |

| LOWER CROSSED SYNDROME | ( 5 ) | 🡪 | ( H ) | A postural pattern in which muscles of the core, back and legs are out of balance; may present as posterior pelvic crossed syndrome or anterior pelvic crossed syndrome |

| SWAYBACK / HOLLOW BACK / SADDLE BACK | ( 6 ) | 🡪 | ( A ) | Other names for hyperlordosis |

| THORACIC KYPHOSIS | ( 7 ) | 🡪 | ( G ) | Another name for kyphosis |

| UPPER CROSSED SYNDROME | ( 8 ) | 🡪 | ( C ) | A postural pattern in which muscles around the shoulder girdle are out of balance; may appear as rounded shoulders and upper back, winging shoulder blades and a forward head |

- Name 15 issues related to the spine that various students might exhibit.

- Muscular imbalances such as upper and lower crossed syndrome

- Hyperlordosis

- Forward head

- Kyphosis

- Thoracic immobility

- Rounded shoulders

- Rib thrust / Rib shear

- Winging shoulder blades

- Excessive anterior pelvic tilt

- Q Angle issues

- Knee hyperextension or poor knee tracking

- Excessive pelvic tucking

- Flattened low back

- Overpronation of feet and/or flattened foot arches

- Misaligned vertebrae

- For what functional reason does the thoracic spine have limited mobility?

- The thoracic spine has limited mobility in order to protect the lungs and heart. Excess motion could impact these key organs.

- What are potential consequences of lack of healthy mobility in the thoracic spine?

- Without healthy mobility in the thoracic spine, then the more mobile areas of the spine (low back and neck) may be recruited and put at risk for injury.

- Another consequence of thoracic mobility issues may be an impact on breathing.

- What are potential causes of hyperlordosis?

Potential causes of hyperlordosis include:

- Structural issues such as flat feet or a short leg

- Abnormal bone growth

- Neuromuscular disorders such as cerebral palsy

- Spondylolisthesis

- Osteoporosis

- Hip dislocation

- Excess weight

- Kyphosis

- Disc degeneration or inflammation

- Weak or imbalanced muscles

- What is kyphosis? Describe potential symptoms.

- Kyphosis is excessive forward curvature of the thoracic spine (clinically defined as greater than 50 degrees).

- Potential symptoms include an appearance of hunching forward, mild to severe back pain, loss of height, difficulty standing upright, and fatigue.

- What are potential causes of kyphosis?

Potential causes of kyphosis include:

- Vertebral fracture due to osteoporosis

- Congenital malformation of the spinal column

- Neuromuscular diseases such as Cerebral Palsy or Scheuermann’s Disease (occurring in adolescents)

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Degenerative conditions due to wear-and-tear such as spinal arthritis with degeneration of discs

- Poor posture and slouching

- What is scoliosis?

- Scoliosis is an abnormal curve from side-to-side.

- What is the difference between structural scoliosis and functional scoliosis?

- Structural Scoliosis is inherited.

- Functional Scoliosis is developed from one-sided activities.

Spine & Back Teaching Considerations

Answer Key

- What are two primary objectives of asana that relate to the spine?

- Move the spine through its full range of motion.

- Restore and preserve the natural curves of the spine.

- What is compensation as it relates to spinal curves and why is it important?

- The cervical and lumbar spinal curves are called “sympathetic,” indicating that when we move one, we tend to move the other as well. That is, when a student flexes her neck, she is likely to flex her low back as well, and when extending the low back, she will often also extend the neck.

- To obtain the intended effects of practice, students need to develop an understanding of the relationship between the curves and this tendency to compensate.

- What three foundational teachings related to the spine might you consider conveying to your students?

- Teach students to feel the natural curves of the spine.

- Teach students to see how compensation works during their own movement patterns.

- Invite increased awareness of habitual movement patterns and learning new ones.

- How might you teach students to feel their natural spinal curves?

- You may wish to use Tadasana, Virasana (on props) and/or Savasana variations to teach students how to feel their natural spinal curves.

- Tadasana (Mountain Pose) is often used to help students gain awareness of their posture and habits as well as to teach actions that help bring alignment and balance. For instance, aligning the pelvis in Tadasana endeavors to find equal hip height, neutral pelvic tilt, neutral front-to-back placement and the pelvis pointing straight ahead.

- Another option for helping students to feel their neutral spinal curves is through teaching Virasana (Hero Pose) or other meditation seats (using plenty of props).

- Describe a simple exercise for students to learn more about their particular body and potential compensation patterns.

- Lie down on the back, stretching arms overhead.

- Inhale, lengthen arms and feet away from each other.

- Exhale, relax.

- Repeat, noticing how the spinal curves change shape during lengthening: most likely the thoracic spine flattens and the lumbar curve deepens.

- What are two common compensation-related issues?

- Excessively arching the low back.

- Straining shoulders and neck.

- What teachings can help students to address common compensation-related issues?

- To avoid excessive low back arching, teach awareness of the pelvis and core engagement.

- To relieve neck and shoulder strain, teach awareness of the thoracic spine and engage in warm-ups prior to poses that require holding the arms overhead, especially in weight-bearing poses such as Downward Facing Dog Pose.

Core Form & Function

Answer Key

Vocabulary Mix & Match

| CORE MUSCLES (1) | 🡪 | (C) | Muscles that stabilize the spine and pelvis |

| ERECTOR SPINAE (SPINAL ERECTORS) (2) | 🡪 | (E) | Three groups of muscles that run the length of either side of the spine, helping to maintain erect posture |

| MULTIFIDUS MUSCLES (3) | 🡪 | (A) | A series of deep muscles that run the length of the spine, stabilizing vertebrae and assisting in spinal rotation and extension |

| SUPERFICIAL ABDOMINALS (4) | 🡪 | (B) | Rectus abdominis, internal obliques and external obliques |

| TRANSVERSUS ABDOMINIS (5) | 🡪 | (D) | Deep core muscle that wraps around torso and supports spine |

- What comprises the core?

The term “core” is used inconsistently. Essentially, it is used to refer to many muscles that stabilize the spine and pelvis.

- The term “core” often refers to the abdominal muscles (outer and deep) and the deep back muscles, including the erector spinae and multifidus.

- More refined definitions also include the diaphragm, pelvic floor and psoas.

- Some definitions include the inner thighs and/or more muscles.

- Describe four functions of the core.

- Contains and protects the internal organs

- Ensures greater mobility of the spine and trunk

- Stabilizes the top part of the body over the bottom part

- Controls the pelvic-lumbar relationship

- List components of the core.

As noted, there are various ways the core is defined. Here’s an overview of muscles to consider for your working definition.

Superficial / Outermost Abdominals

- Rectus abdominis

- Internal and external obliques

Deep Abdominals

- Transversus abdominis (TA)

Deep Back Muscles

- Erector spinae (spinal erectors)

- Quadratus lumborum (QL)

- Multifidus muscles

More

- Diaphragm

- Pelvic floor

- Psoas

- What does the rectus abdominis do? Gives example of asanas that strengthen and stretch it.

- Bends spine forward

- Worked in Navasana and Bakasana / Kakasana.

- Lengthened in Urdhva Dhanurasana.

- What do the obliques do? Provide an example of asana that work them.

- Twists torso and bends it sideways

- Worked in Jathara Parivartanasana, Ardha Matsyendrasana, Vasisthasana and Parivrtta Trikonasana.

- What does the TA do? What is an example of an asana that works it?

- Wraps around torso and supports spine

- Worked in Plank Pose.

- What are the deep back muscles and how do they relate to the core?

- The deep (or intrinsic) back muscles are the erector spinae, quadratus lumborum (QL) and multifidus. They are covered by deep fascia.

- The deep back muscles are considered part of the core musculature.

- See detailed information in Anatomy of Back Muscles.

- Define and discuss the significance of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP).

- Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) refers to the “pressure chamber” located in our trunk between the diaphragm, pelvic floor and abdominal walls.